Introduction

The promise of “Non-Fungible-Tokens” (or NFTs) is to extend the notion of provable, traceable, and immutable ownership rights deeper into the digital realm, regardless of the fungibility or tangibility of a given asset. NFTs have the ability to further democratize the creator economy, shifting the balance of power away from intermediaries and/or gatekeepers that have historically extracted value from the processes of art creation, curation and distribution. More broadly, the technological underpinnings of NFTs are increasingly being applied to alternative use cases for digital ownership outside of digital art and/or collectibles.

Market Size

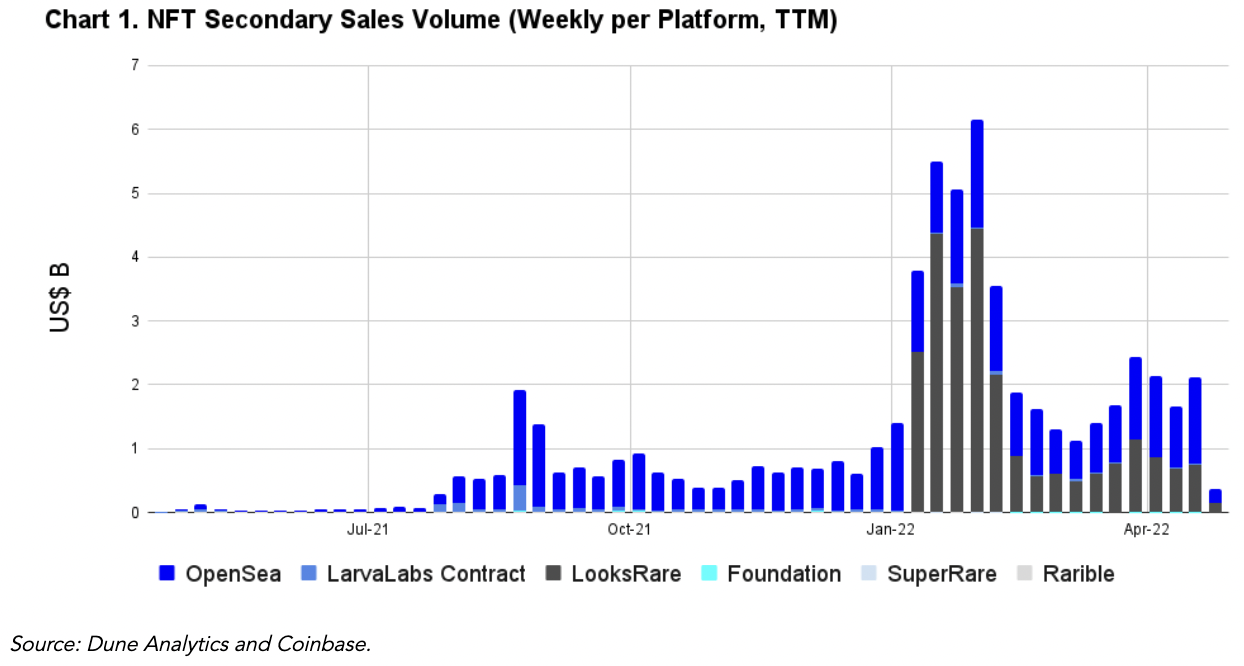

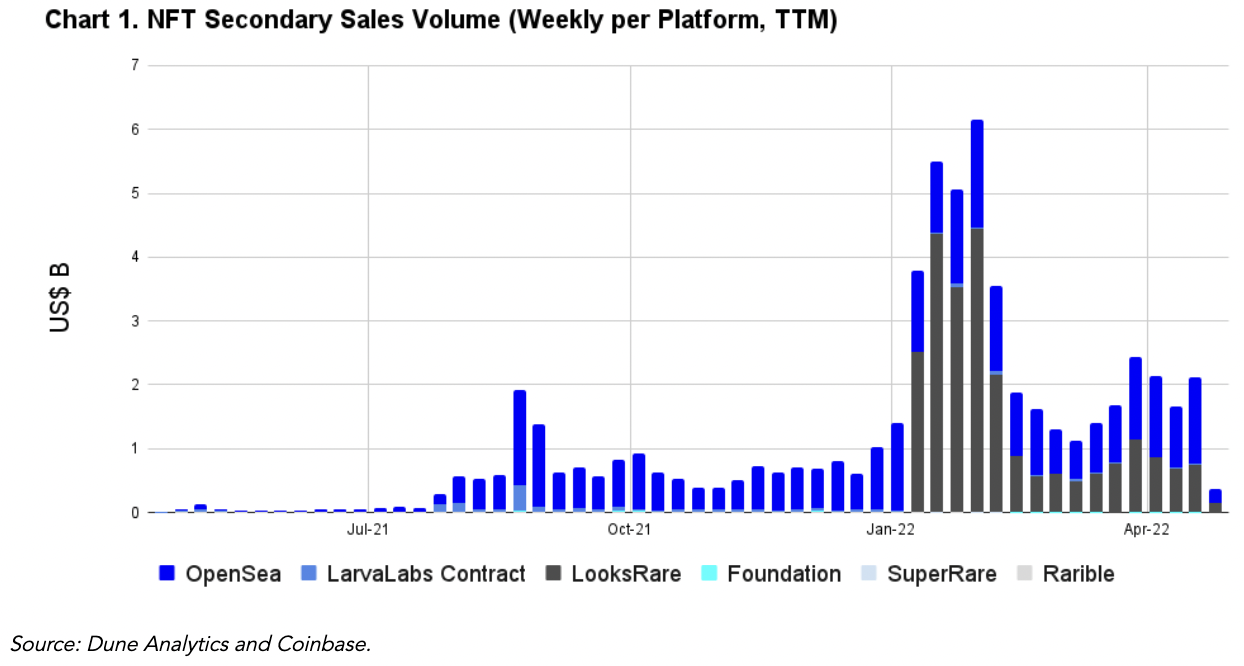

While the very first NFTs were minted in 2014 (on bitcoin) and later in 2015 (on Ethereum), the space remained a sub-niche of the broader crypto market until early 2021 when significant capital began flowing into “digital collectibles.” Prior to 2021, the historical cumulative secondary sales volume for NFTs was approximately US$70M. As NFTs have entered mainstream consciousness over the past eighteen months, the cumulative sales volume processed across secondary marketplaces has risen roughly ten-fold to over US$60B.

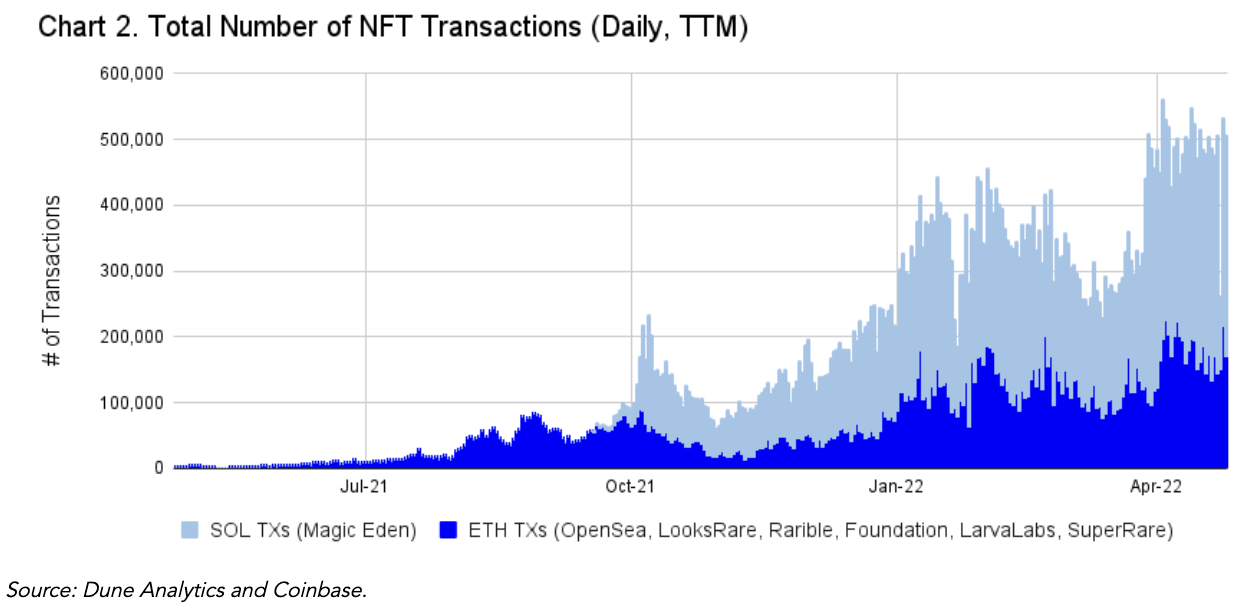

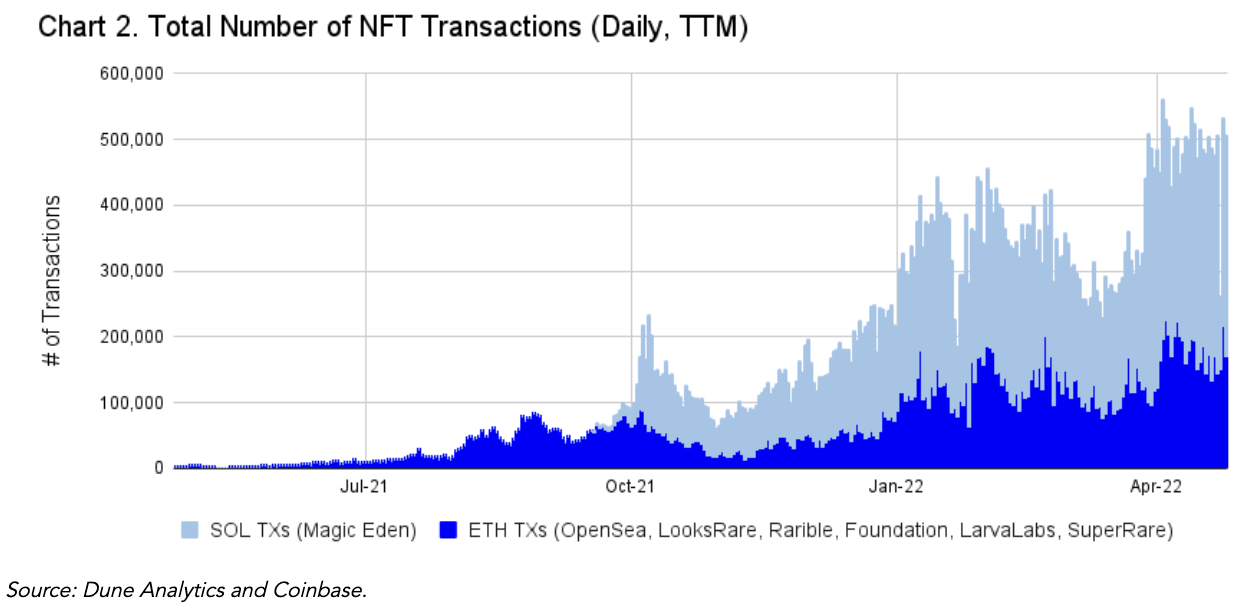

This immense growth in volume has been spurred by a growing community of artists, collectors, and investors, which in aggregate have executed over 30 million transactions across 4.6 million unique crypto wallets and currently represent over 350,000 monthly active users across both Ethereum and Solana secondary marketplaces (according to Dune Analytics). It should be noted that these numbers are conservative as they do not include primary sales volumes. Further, while the table below depicts a higher level of daily transactions on Solana in recent months, this is largely a function of significantly smaller average purchase prices for NFTs on Solana, as well as lower fees for processing transactions. In US$ terms, NFT sales volumes are still dominated by Ethereum, as the total cumulative US$ volume on Solana secondary markets totaled just under US$1B over the last six months.

Unsurprisingly, this rapid market growth has prompted an influx of new NFT projects into the ecosystem, the vast majority of which could be considered low-effort money-grabs or simple derivatives of existing established collections. Recent estimates suggest there are nearly 100,000 NFT projects in existence today. Accordingly, it is important for any sophisticated investor attempting to enter this space to be aware of the concentration of activity in what could be considered “top tier” or “blue chip” NFT collections.

Where to begin?

Arguably the most important metric in analyzing a given NFT collection is its level of historical secondary sales volume, which serves as a useful barometer for meaningful interest and/or conviction in a project. All else equal, strong and sustainable secondary sales volume is the primary driver of the “floor price��” or the price of the cheapest available NFT within a given collection. Further, strong secondary sales volume can be viewed as a proxy for the go-forward liquidity of a given NFT collection.

In other words, the higher the level of historical secondary sales volume and the higher the floor price, the more “liquid” a given NFT collection may be. Other factors which may impact the liquidity of a given NFT collection include the supply cap of the collection (collections with limited supply naturally tend to be less liquid) and the economic interests of the existing holder base (short-term vs. long-term investment horizons). It should be noted that while higher levels of liquidity are generally a positive indicator of the growth trajectory of a given NFT collection, the inverse is not necessarily true. A given NFT collection that would otherwise constitute an attractive investment opportunity might be relatively illiquid due to a small supply cap and/or a holder base consisting of investors with a longer term horizon. In this instance, the illiquidity of the collection may actually be a positive near-to-medium term catalyst for the floor price, so long as new demand for the collection continues to outstrip the supply of willing sellers.

The market dynamics which characterize NFTs differ significantly from the broader crypto-asset market in that in order to liquidate an investment, the seller must find a specific buyer for their specific NFT. For instance, while a motivated seller might be able to quickly liquidate a Bored Ape by listing it at/near the floor price, the same could not be said for an NFT from a collection with lower levels of historical volume. The seller might even be willing to undercut the current floor price significantly and still not be able to find a willing buyer (potentially leading to a downward spiral in floor price as more sellers undercut the floor while demand remains stagnant).

In practice, this suggests that NFT collections with greater liquidity may provide investors with a higher level of downside protection in times of broader market turbulence and/or fluctuating demand for NFTs, relative to collections with lower liquidity. Conversely, attempting to invest in NFT collections which lack a robust track record of secondary sales volume and resultant liquidity often implies an investor’s willingness to move farther out along the risk curve. Minting new projects (primary sales) could be considered the most risky end of that spectrum, while investing in more established “blue chip” NFT collections represents the most risk-averse end of that spectrum.

Although there are ~100,000 projects in existence, institutional investors with an average risk appetite could likely eliminate over 95.3% of the NFT collections in existence from consideration based on the historical strength of secondary sales volume alone (see chart 3). CryptoPunks and Bored Apes, the two most prominent NFT collections in existence, boast historical secondary sales volumes of 895,466 ETH and 510,121 ETH, respectively. This level of concentration in collections with strong historical secondary sales volume and resultant levels of higher liquidity suggest that the “investable universe” for the majority of institutional players is likely far more narrow than most realize.

Categorizing NFTs

Despite the nearly infinite universe of potential use cases for NFTs (more on this later), the vast majority of historical transaction volume has been targeted towards various forms of digital art/collectibles. That being said, the narratives surrounding which specific subcategories of NFTs should or could accrue the most value are both nuanced and adaptable.

The prominent narrative driving NFT purchase volumes over the past eighteen months has largely oscillated between the fundamental attributes of aesthetics, historical significance and proposed utility. These pillars are described in greater detail in the table below. While not necessarily mutually exclusive (i.e. utility-focused projects may also have attractive aesthetics), most digital art/collectible NFTs fall primarily into one of these three categories.

Deriving Value

This segmentation is useful in constructing measurable criteria to evaluate a given NFT project. Different subcategories of NFTs tend to require different due diligence criteria. For instance, the analysis of a long-form generative art (i.e. art created through the use of autonomous systems) collection differs significantly from the analysis of a 10k profile picture (PFP) collection promising holders access to incremental future value.

Perhaps the most straightforward set of criteria pertains to historically significant NFTs, such as Rare Pepes, Ether Rocks and CryptoPunks. In short, the earliest projects ever minted on the blockchain should in theory command meaningful value, derived primarily from scarcity and the notion that these early projects are important artifacts of this new medium for art.

Artists that produce 1-of-1 pieces, like XCOPY and Beeple, can be viewed most similarly to their traditional art market analogs, as they are purely focused on creating art and memorializing it on the blockchain, benefiting from programmable royalties inherent to NFTs.

For long-form generative art, popularized by platforms such as Art Blocks and FXHASH, value potentially stems not only from aesthetic appeal, but also from the elegance of the code that produces a cohesive, yet diverse, set of random outputs.

Likely the most multifaceted set of criteria pertains to NFTs promoting some form of “utility” for its holders. Most PFP/avatar projects, such as the Bored Ape Yacht Club (BAYC), would fall into this category, as well as certain token-based membership passes like PROOF collective. Value in this category may be derived from the level of community engagement across social channels, a proposed reward system or token airdrop, and access to gated online communities or in-real-life (IRL) events.

Separately, there are certain characteristics which could signal a given NFT collection is “high quality” that could apply to all of these subcategories. Elements such as the aforementioned historical secondary sales volume, a widely distributed holder base, a reasonable initial mint price and artist royalty percentage, are typically positive signals of organic traction for a given project.

Further, within a given collection, certain NFTs which are more scarce (i.e. unique or rare) may command higher values than their “common” counterparts. Trait-based rarity systems are common across both PFP collections and long-form generative art collections, with the most unique and scarce combinations within a collection typically demanding a price premium over the rest of the collection.

Beyond Monkey JPEGs

“Utility” can be an overused term in crypto, but in the most primitive sense, the utility of a given NFT is the blockchain-enabled ownership rights embedded in the asset itself. The inherent transparency and immutability of the asset are technical improvements over existing forms of ownership in the digital realm. Over time, however, utility has come to represent far more than these technical improvements over Web2 property rights. Initially, one could argue the utility of the most basic PFP/avatar projects was the ability to represent oneself online with a provably unique image, while potentially serving as a status symbol. Utility nowadays suggests potential yield, access to metaverse and/or IRL events/groups, future airdrops, grants to digital land, or access to items/boosts for gaming.

The “flippening” (in terms of floor price) of Bored Apes over CryptoPunks, which occurred in December of 2021, and the subsequent acquisition of CryptoPunks by Yuga Labs (the parent company of BAYC) in March of this year, could be viewed as a microcosm of this more recent narrative shift towards “utility” based NFTs. While CryptoPunks were able to lean on their historical value and provenance (having been minted in 2017 for free), the BAYC launched in April 2021 and explicitly aimed to provide more than just a singular PFP to its buyers.

Their utility-focused strategy has included a variety of member-only benefits such as subsequent free mints (Bored Ape Kennel Club and Mutant Ape Yacht Club), an airdropped token ($APE), merchandise, videogames and access to real-life events. Importantly, Yuga Labs also made the decision to grant its holders the actual IP rights associated with their specific Bored Ape, allowing them to personally profit from potential licensing deals (something that Larva Labs failed to provide for CryptoPunk holders prior to Yuga Lab’s acquisition).

This preference for more than just a singular JPEG is arguably indicative of the maturation of the ecosystem and may reflect the realization by market participants that the technical underpinnings of NFTs can and will increasingly be applied to more than just art/collectibles. Further, because art/aesthetics are quite subjective at the end of the day, by shifting the focus towards the purported utility of a given NFT, market participants may feel as if they can construct a more robust qualitative/quantitative basis for an investment through more directly measurable criteria.

Conclusions

Today’s NFTs are presenting the archetype for how ownership should work in the digital economy and creating the roadmap for new and innovative use cases outside of art/collectibles, including but not limited to:

- Digital Identity

- Ticketing

- Memberships/Subscriptions

- Physical Luxury Goods

- Supply Chain/Logistics

- Music IP/Royalties

- Fractionalized Assets

- Gaming Items/Boosts

- Digital Land

Most of these proposed alternative use cases listed above represent disruptive infrastructure plays targeting existing industries yet to adopt crypto-native solutions. With the possible exceptions of gaming-focused NFTs and digital land, the value created in these subsegments is likely to be largely captured by corporates and VCs, as opposed to the average retail investor.

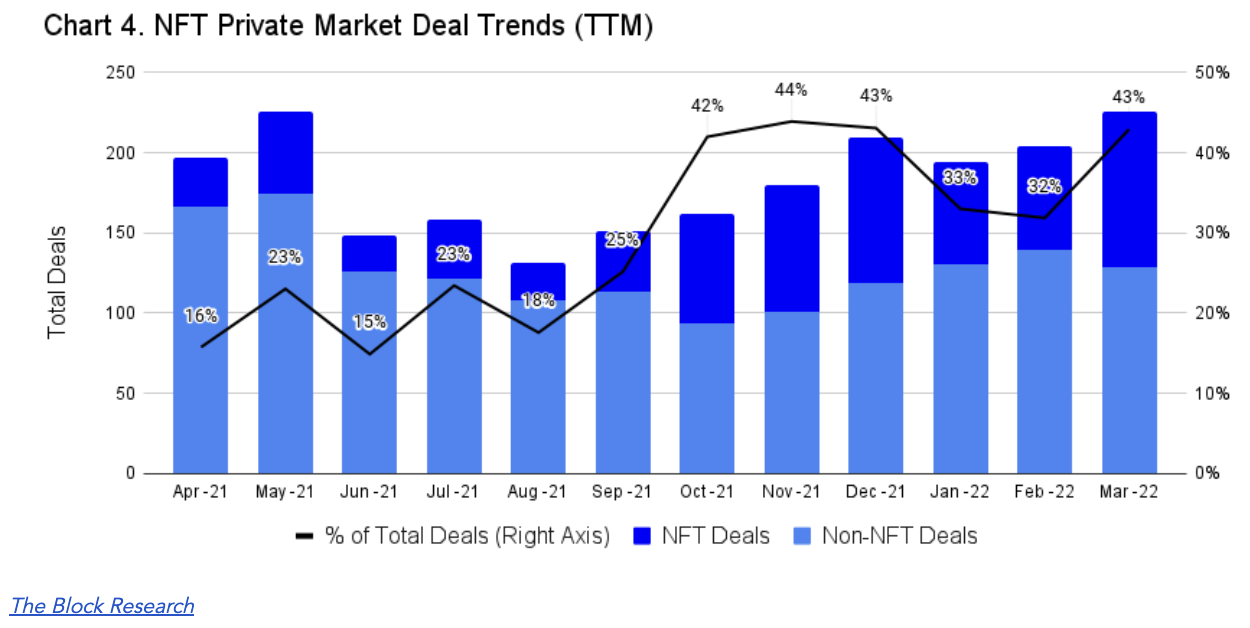

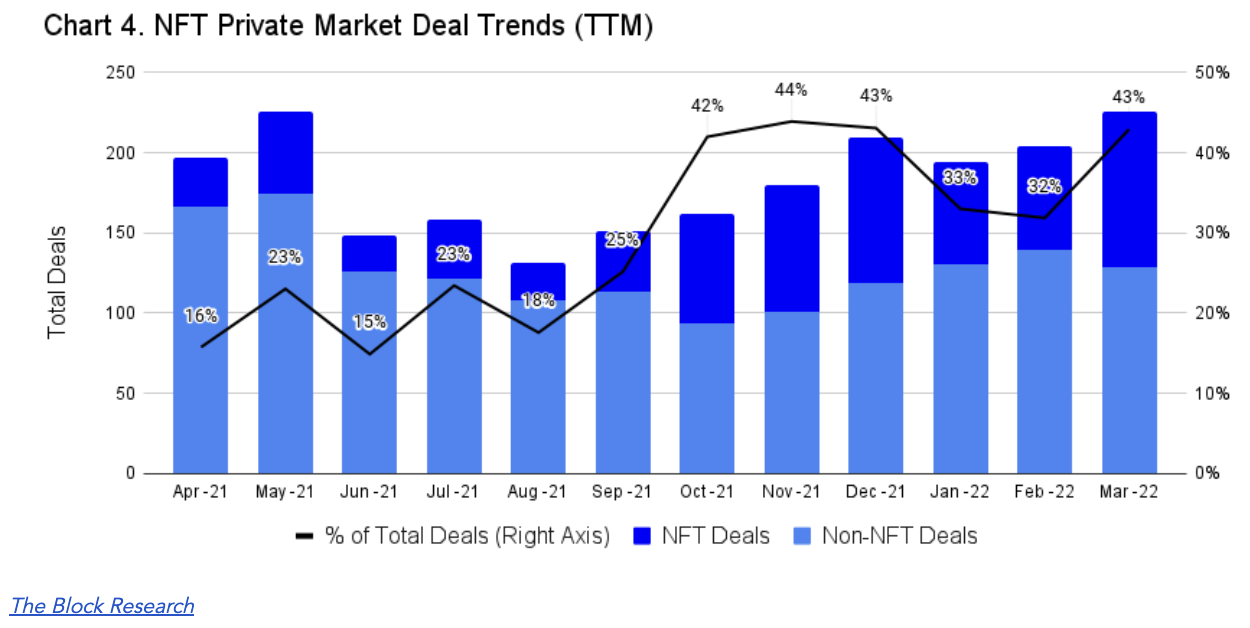

While it may be difficult to gauge institutional involvement in specific NFT collections, capital is being deployed to support the broader NFT ecosystem and build out the infrastructure that will allow more use cases for NFTs to flourish. Over the trailing twelve months (TTM), there have been over 2,100 Blockchain/Crypto Venture deals executed, 30% of which were in the NFT space, representing over US$8B of investment. Directionally speaking, the share of deals oriented towards the NFT space is increasing over the TTM, with ~15% of deals being allocated to the NFT space in April 2021 compared to ~43% of deals being allocated to the NFT space in March 2022.

In our view, alternative use cases for NFTs haven't received the same level of mainstream attention as profile pictures (PFPs). For the average retail investor, the strategic emphasis has been placed on identifying and minting the next 100x PFP project. From an institutional investor’s perspective, however, investing in the infrastructure of the NFT space and ultimately implementing frameworks like we’ve presented in this report to invest in “high quality” NFT collections, represent far more risk averse strategies.

Further, a handful of startups are focused on building tools for NFT-based borrowing/lending as well as fractionalization, all of which promise to increase the level of liquidity across the space. While still in their early stages, several new platforms are focused primarily on allowing users to post their NFTs as collateral for crypto-based loans. The broader financialization of the NFT space should allow for greater levels of liquidity as the industry matures.